BARDOLPH: And of women.

Henry V act 3, scene 2

HOSTESS: Nay, that he did not.

BOY: Yes, that he did, and said they were devils incarnate.

HOSTESS: ‘a never could abide carnation. ’twas a color he never liked.

DOUBLE POST DOUBLE POST

This is your periodic reminder that I adore Henry V and you should too. And also a reminder that it might seem like I’m talking down to you here, but I promise I just sound like a patronizing dick all the time and it’s nothing personal.

So I talked in my last post a bit about inkhorn terms (words imported from Latin at the tail end of the 1500s to fancify English) and how Shakespeare glosses his own lines for his listeners, and I wanted to give an in-depth example of that, for funsies. And what better example than the most famous “what the fuck is he saying?” line, from Macbeth:

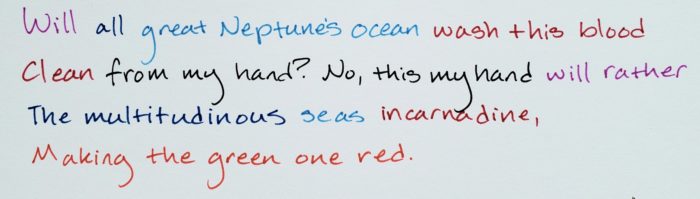

Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood

Clean from my hand? No, this my hand will rather

The multitudinous seas incarnadine,

Making the green one red.

Usually when people quote it all they quote is “the multitudinous seas incarnadine,” which… duh, of course it’s not going to make any sense. If you leave out “will,” then “incarnadine” sounds like an adjective and there’s no context to tell us what it might mean. But if you have the full quote, it’s easy to pair it up with other words and figure it out.

Often when Shakespeare does this doubling-up thing, he does it like mirror. So you start with “from my hand? // No, this my hand will rather” – and since will… // will rather makes it clear that the second sentence is a direct refutation of the first, you can assume that what comes next will just be the first sentence again, just in negative.

So:

If seas pairs with ocean, then multitudinous must pair with all. Easy enough. And if you think about it, multitudinous actually makes sense on its own: it’s just multitude + the (n)ous ending that adjectives sometimes get when they’re derived from a noun – riotous, furious, suspicious, wondrous, capricious. So we don’t actually need “all,” and neither did Shakespeare’s audience, since multitude entered English in the early 1300s. But it sets us up to understand that the second sentence really is just going to be a mirror of the first.

But ocean and seas are both actually part of larger phrases. All great Neptune’s ocean won’t wash this blood clean from my hand; instead, that hand will those multitudinous seas incarnadine. In context, incarnadine is obviously a verb, and it’s the inverse of wash clean (of blood).

So we get the general idea of the sentence, but we really only know what incarnadine means in opposition to other words, not on its own. So Shakespeare spells it out for us.

We’ve completed our two parallel sentences; there isn’t anything left to compare. So making the green one red must then be directly modifying the verb before it, which we now know to be incarnadine. And if we assume that the sea is green, and we know that blood is red, it becomes obvious: to incarnadine is to make red.

I made a visual representation too, because I like pretty markers and this post felt too short: 1

When you look at it written out like that you can see just how parallel it is and how it all leads up to that fun-but-ambiguous incarnadine. You kind of get the sense he just really wanted to use it and orchestrated a sentence that would let him do it.

And here’s the thing: some of Shakespeare’s audience would have understood exactly what incarnadine meant without all that, because it was already an adjective. It meant flesh-colored or carnation-colored and it has the same root as incarnate (“made flesh”). Incarnadine as an adjective is only attested from the 1590s, so it’s one of those inkhorn words Shakespeare was so fond of. But for the rest of them (and us), Shakespeare tacks on a definition.

Shakespeare knows his sentences can be impenetrable. He’s twisting English into shapes it doesn’t normally take and using words it doesn’t normally use. But a playwright doesn’t become successful if no one understands what he’s saying. If you’re using multitudinous seas incarnadine as an example of why Shakespeare is hard to understand, you’re actually just demonstrating how brilliant he is.

Notes:

- Huge shoutout to I believe my friend Tess who gave me this Staedler 20-pack set of pens for my 13th birthday that I still use to this day. They look ugly in this picture but I promise they’re great. ↩